This engagement marked the decisive close to the Second English Civil War. Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army faced a combined Royalist force, largely Scottish Engagers, in a pursuit that turned into a rout and sealed the fate of the militarised uprising.

Background

Charles I had sought to regain his throne by negotiating with a faction of Scots, known as the Engagers, who agreed to assist him in return for ecclesiastical concessions. In response, Cromwell marched north and met Hamilton’s army around Preston.

According to contemporary accounts, “[in] one skirmish the commander of their advance guard was killed,” underlining the fierce resistance Cromwell faced even in pursuit.

Forces

Leaders

Parliamentarians (New Model Army / Northern Association / Lancashire Militia)

- Oliver Cromwell commanded the main New Model Army.

- John Lambert led Northern Association forces.

- Regional militia under various local commanders.

Royalists (Scottish Engagers with English Royalist support)

- Duke of Hamilton led the main Scottish Engager army.

- General William Baillie oversaw the infantry contingent.

- Lords Langdale and Musgrave commanded Royalist English elements.

Troop Composition

| Side | Infantry | Cavalry | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parliamentarians | ~5,300 | ~3,700 | Figures include New Model, Lambert’s forces, and militia |

| Royalists | ~18,300 (Scottish) + ~4,500 (Royalist) | ~5,700 total | Not all were engaged; many units understrength |

A contemporary voice, likely exaggerating but telling in tone, claimed “not a fifth man could handle a pike,” a comment aimed at the poor training and morale of many Scottish troops.

Arms and Armour

Infantry were organised into regiments of musketeers and pikemen. Musketeers used four-foot, matchlock muskets, with some flintlock variants, while pikemen wielded 15–18-foot pikes, often bearing body armour and helmets.

Cavalry on both sides wore pot helmets, thigh-length boots and cuirasses or leather jerkins. Parliamentarian horsemen typically carried two pistols and a sword, their flintlocks offering better reliability in rain. Scots often bore lances instead of pistols, useful in open warfare but clumsy in Preston’s broken terrain.

Dragoons had become specialised mounted troops by 1648, some using carbines, while the Scots still clung to older matchlock muskets.

At the Battle of Preston in August 1648, the types of swords in use reflected the mixed composition of the armies and the transitional nature of mid-17th-century warfare. While firearms, pikes, and polearms dominated the battlefield, swords were still an essential sidearm for officers, cavalry, and some infantry.

Parliamentarian New Model Army and Northern Association forces

- Mortuary swords: A distinctly English cavalry weapon, with a broad, double-edged blade, basket hilt, and decorative pommel often bearing a portrait mask. Common among Parliamentarian officers and troopers.

- Baskethilt broadswords: These were increasingly common for both horse and foot soldiers, offering hand protection in close combat.

- Rapiers: Mostly carried by officers and gentlemen; long, slender, and more suited to duelling or command presence than mass battle.

- Hangers: Short, curved blades often worn by dragoons or militia for camp defence and as a secondary weapon.

Royalist Scottish Engager and English Royalist forces

- Scottish baskethilt broadswords: Sometimes called “claymores” in this period (the single-handed type, not the later two-handed highland sword). These were robust, double-edged, and ideal for hacking in close quarters.

- Mortuary swords: Carried by many English Royalist cavalrymen, similar to those of the Parliamentarians.

- Rapiers: Present among officers, especially in the English Royalist contingents.

- Dirks and daggers: Secondary blades often carried by Scots alongside their broadswords.

Although pikes and muskets were the primary arms of infantry, when formations collapsed—such as in the close fighting at Ribbleton Moor and Winwick—these swords became decisive in the hand-to-hand engagements.

Archaeology

No major modern excavations of the battlefield are recorded in mainstream sources, so physical evidence remains largely in local museums, such as the Warrington Museum, which houses artefacts like musket balls and possibly frame-gun shot dating from the conflict. These finds hint at the intense close-quarters fighting, especially around Walton and Winwick.

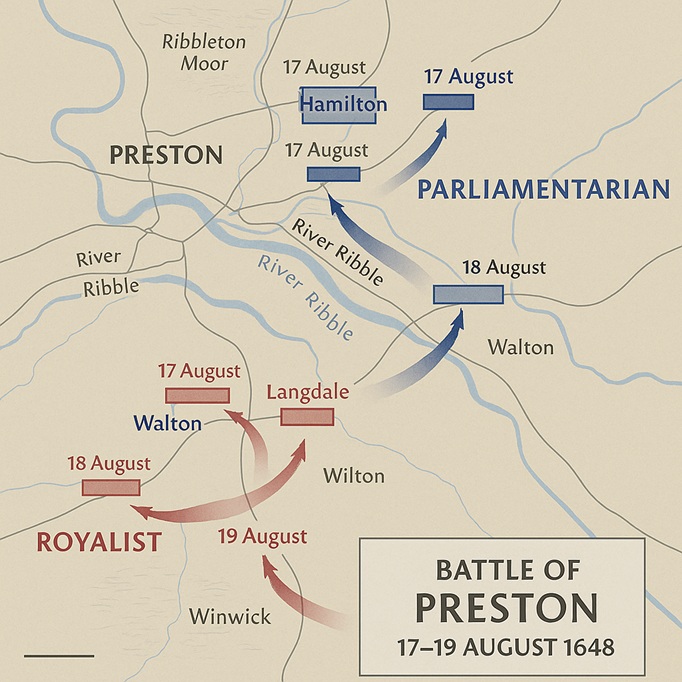

Battle Timeline

17 August

Cromwell surprised Hamilton’s scattered forces around Ribbleton Moor. Langdale’s infantry formed a defensive line that held off Parliamentarian cavalry with pikemen. After fierce combat, what Cromwell termed “a very stiff and sturdy resistance,” Parliamentarian infantry and local militia cracked the line and swept toward the Ribble bridge, forcing a breakthrough.

Evening of 17 August

Thousands of Scots were captured as fields became littered with prisoners. Royalists regrouped south of the river as Parliamentarians secured the bridge and surrounding approaches. Cromwell declared the enemy “broken” in a letter.

18 August

The Scots escaped south in the night, abandoning artillery, baggage and ammunition. The Parliamentarians pressed on relentlessly, catching and disrupting the retreat.

19 August (Battle of Winwick)

Exhausted but cornered, the Scots halted near Winwick. Fierce fighting ensued. Parliamentarian cavalry pinned Scots in place while infantry attacked from the flanks. Formations broke and many fled into the church at Winwick, where they surrendered. The Scottish cavalry slipped away but many surrendered in Warrington and Uttoxeter soon after.

Contemporary Reflections

Cromwell estimated “2,000 Royalists were killed and 9,000 captured,” though historians suggest such figures are inflated. Modern estimates put Royalist deaths around 1,000 at Preston, with 4,000 prisoners; the broader campaign, including Winwick, added about 1,000 killed and 7,000–8,000 taken prisoner.

One Scots officer, overwhelmed, “beseeched any that would to shoot him through the head,” a vivid testament to the despair of the defeated leadership.

Aftermath and Perspective

The battle effectively ended organised Scottish military support for the Royalists in this war. Hundreds of prisoners were sold or pressed into service overseas. Hamilton was subsequently beheaded. The execution of Charles I followed not long after. England became a republic under the Commonwealth, while Scotland ultimately fell under Cromwell’s rule.

Watch the documentary: