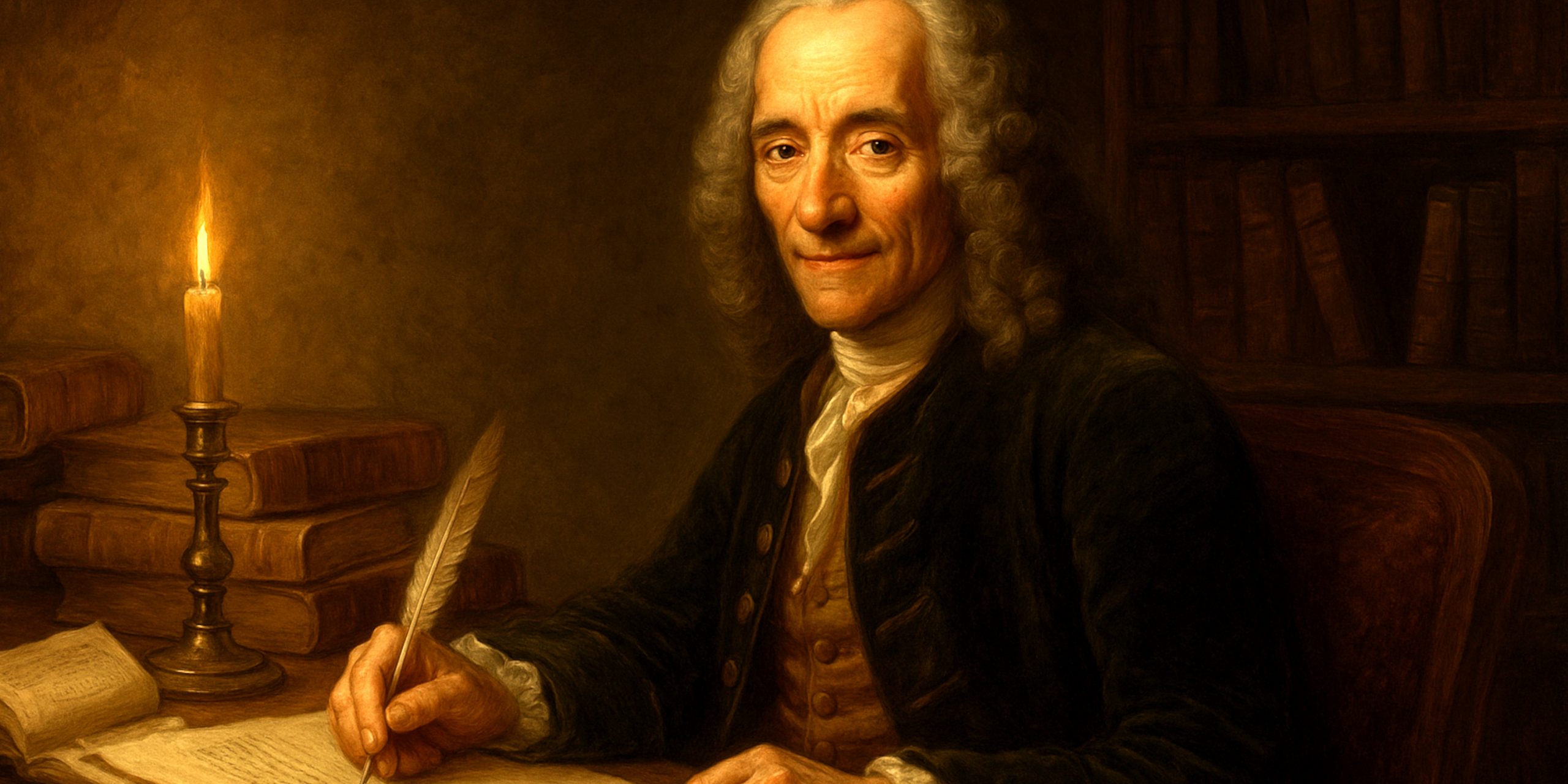

Voltaire was not a man to stay quiet. Born François-Marie Arouet in 1694, he became the Enlightenment’s most notorious agitator, writer, and wit. His pen, more than any sword of his time, carved deep wounds into the rigid flesh of dogma and despotism. If the Age of Reason had a spokesperson, it was Voltaire, a man who believed the world could be improved if only people would stop being so certain of their own righteousness.

Early Life and Education

Born in Paris to a family that wanted him to become a lawyer, Voltaire instead chose the far riskier path of words. Educated by Jesuits, he absorbed both the structure of classical thought and a lifelong suspicion of religious authority. By his twenties, he had already earned the attention of the powerful and the irritation of nearly everyone else.

His early satirical verses mocked the French elite, earning him a brief stay in the Bastille in 1717. Voltaire used the experience as fuel, emerging sharper and bolder. He adopted his pen name and started the lifelong act of turning exile and disgrace into publicity.

The Philosopher of Wit

Voltaire never confined himself to one medium. He wrote plays, essays, poems, and histories, but his enduring power lay in his relentless criticism of ignorance and injustice. His style was clean, quick, and deadly. Where other philosophers lectured, Voltaire skewered.

He defended freedom of speech long before it became fashionable, declaring, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” (Though the quote was likely summarised by later biographers, the sentiment fits him perfectly.) He detested fanaticism, writing Candide in 1759 to mock the idea that “all is for the best” in a world brimming with absurd cruelty.

Exile and Correspondence

Voltaire spent much of his life in voluntary exile, often because his words had made Paris uninhabitable. He fled to England in the 1720s, where he discovered constitutional monarchy, Locke, and the freedom to publish ideas without fear of imprisonment. These experiences deeply shaped his belief that progress required tolerance and open debate.

Later, in Switzerland and at his estate in Ferney, he corresponded with Europe’s thinkers, scientists, and even monarchs. Frederick the Great of Prussia was both friend and rival, their relationship oscillating between admiration and irritation, two emotions Voltaire inspired in abundance.

Philosophy and Beliefs

Voltaire’s philosophy was not systematic like Descartes or Kant. He was more a provocateur than a builder of grand theories. Yet his principles were clear enough:

- Reason over superstition. He saw religion as a social necessity corrupted by fanaticism.

- Freedom of thought. No authority, divine or royal, should dictate what one may think or say.

- Justice and reform. He opposed torture, censorship, and persecution, often intervening personally in legal cases such as the wrongful execution of Jean Calas.

He believed in deism, a rational faith that acknowledged a creator but rejected organised religion’s claim to absolute truth.

Legacy

Voltaire lived to see the early tremors of the French Revolution he had helped inspire, though he died in 1778 before it erupted. His writings outlived the monarchy that exiled him, and his remains were transferred to the Panthéon in 1791, symbolically enshrining reason over tyranny.

His influence rippled through modern liberalism, human rights, and the scientific spirit. He proved that mockery, when aimed at the powerful, could be a moral weapon.

Today, his name still conjures both admiration and unease. He was not gentle, nor always right, but he was never dull. Voltaire understood that to challenge the world, one must first dare to laugh at it.

Selected Works

| Work | Year | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Oedipus | 1718 | Early play that established Voltaire’s literary reputation. |

| Letters Concerning the English Nation | 1733 | Introduced English liberal ideas to France. |

| Candide | 1759 | Satirical masterpiece exposing the absurdities of optimism and authority. |

| Philosophical Dictionary | 1764 | Encyclopaedic assault on superstition, fanaticism, and hypocrisy. |

Contemporary Quotes

“Judge a man by his questions rather than by his answers.”

“It is dangerous to be right in matters where established men are wrong.”

Dry as a desert and twice as cutting, Voltaire’s voice remains relevant precisely because the follies he mocked still walk among us.

Watch the documentary: