Catherine Howard is often remembered as the reckless teenage queen who lost her head, literally and reputationally. That version is convenient, dramatic, and deeply incomplete. She was young, politically expendable, and married to a man old enough to be her grandfather who expected obedience and gratitude in equal measure. Her story is less about scandal for its own sake and more about power, surveillance, and how little room Tudor England gave to women who stepped out of line, or were pushed there.

Family Background and Early Life

Catherine came from the powerful but chronically disorganised Howard family, a cadet branch of the Dukes of Norfolk. The Howards had prestige, ambition, and a talent for surviving court politics by shedding relatives when required. Catherine’s father, Lord Edmund Howard, had little money and even less influence. As a result, she was sent to live in the household of her step grandmother, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk.

This was not a finishing school in the polite sense. Supervision was lax, boundaries were flexible, and the dormitories were mixed in ways that would later cause Catherine serious trouble. Relationships formed, secrets were shared, and nobody seemed particularly concerned about the long term consequences. Tudor morality was strict in theory, casual in practice, until it suddenly mattered a great deal.

Arrival at Court

Catherine arrived at court as a maid of honour to Anne of Cleves. She was young, lively, and conspicuously attentive to fashion and charm. Henry VIII noticed her almost immediately. This was not a subtle courtship. Henry had recently rejected Anne of Cleves and was eager to reassure himself that he was still virile, desirable, and very much in charge.

For the Howard faction, Catherine was an opportunity wrapped in silk. A new queen meant influence restored and rivals sidelined. That she was inexperienced and politically untrained was not seen as a drawback. It was the point.

Marriage to Henry VIII

Henry married Catherine in July 1540. He was nearing fifty, increasingly ill, and prone to violent mood swings. She was probably around seventeen. The court celebrated the match with exaggerated enthusiasm, partly from relief after the Anne of Cleves debacle, and partly because nobody wanted to question the king’s taste.

Henry called her his “rose without a thorn”, which reads less romantically when one remembers that he was responsible for the pruning. Catherine played the role expected of her. She smiled, danced, dispensed patronage where guided, and tried to look delighted at all times. The marriage brought her jewels, titles, and attention, but very little autonomy.

Queenship and Court Life

As queen, Catherine had limited political impact. She was not encouraged to develop one. Her household was large, expensive, and closely watched. The court was a place of constant observation, where servants noticed everything and forgot nothing when it became useful.

Catherine appears to have sought comfort and familiarity rather than intrigue. Her behaviour suggests a young woman attempting to navigate intimacy and trust in an environment that offered neither. That she made poor choices is difficult to deny. That she fully understood the danger of those choices is much less certain.

The Allegations

The charges against Catherine were twofold. First, that she had engaged in sexual relationships before her marriage and failed to disclose them. Second, that she had committed adultery as queen. In Tudor law, this amounted to treason.

Evidence came from former members of the Duchess of Norfolk’s household, many of whom had their own reasons for talking. Letters were interpreted in the least generous way possible. Private conversations were treated as confessions. The investigation moved quickly once it began, which is usually a sign that the outcome has already been agreed.

Henry’s reaction was a mix of rage, humiliation, and wounded pride. Mercy was not in fashion, particularly when the king’s masculinity felt under threat.

Trial and Execution

Catherine was never given a formal public trial. Parliament passed an Act of Attainder, which made her guilt a matter of law rather than debate. She was executed at the Tower of London in February 1542.

Eyewitness accounts suggest she was composed on the scaffold. She asked for prayers and acknowledged her failure, although whether this was genuine remorse or survival instinct dressed as piety is impossible to know. At around eighteen or nineteen years old, her life ended quickly, efficiently, and without much interest in nuance.

Reputation and Reassessment

For centuries, Catherine Howard was dismissed as foolish or promiscuous, a cautionary tale rather than a historical figure. Modern scholarship has been less inclined to sneer. Viewed in context, her actions look less like recklessness and more like the consequences of inadequate education, poor guardianship, and an absolute monarchy that confused control with morality.

She was not a schemer on the scale of Anne Boleyn, nor a political survivor like Catherine Parr. She was a teenager placed at the centre of a brutal system and expected to succeed without error. The surprise is not that she failed, but that anyone thought she would not.

Where to See Artefacts and Sites

There are no personal possessions that can be firmly attributed to Catherine with confidence. Her presence is felt instead through places. Hampton Court Palace remains the most evocative. The gallery where she is said to have run towards Henry, unsuccessfully, still encourages a pause, if only to appreciate how quickly favour could turn to silence.

Legacy

Catherine Howard’s legacy is quiet but unsettling. She represents the cost of Tudor power politics when applied to the young and disposable. Her story invites less judgement and more restraint, which is not always the Tudor historian’s default setting.

She was not innocent in every sense, but neither was she given a fair chance to be anything else.

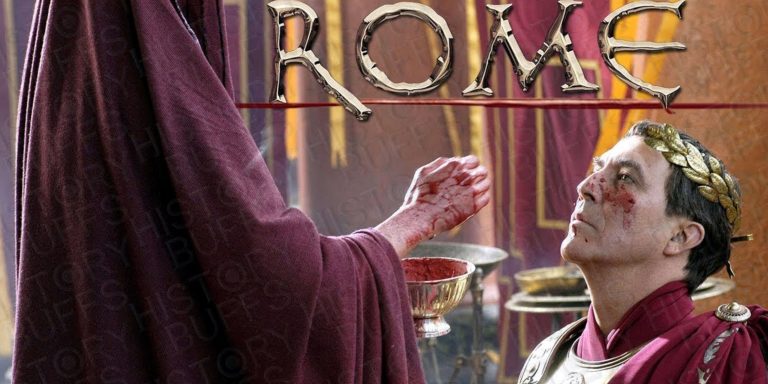

Watch the documentary: