Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus remains one of the most recognisable names in Roman history, and not for reassuring reasons. Even two millennia on, his reputation carries the weight of fire, blood, and theatrical excess. Yet Nero also ruled longer than several of his Julio-Claudian relatives and presided over a period of relative peace on Rome’s frontiers. As with most Roman emperors, the truth sits somewhere between the marble bust and the scandal sheet.

What follows is not a rehabilitation, nor a prosecution. It is an attempt to understand Nero as a ruler, a man, and a product of imperial Rome, with all the contradictions that implies.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Nero was born in AD 37 into a family already steeped in political danger. His mother, Agrippina the Younger, was ambitious, ruthless, and well connected, a combination that rarely ends quietly. Through careful manoeuvring and a strategically placed marriage to Emperor Claudius, Agrippina secured her son’s adoption and eventual succession.

When Nero became emperor in AD 54 at the age of sixteen, Rome exhaled. His early reign was guided by experienced hands, notably Seneca and the praetorian prefect Burrus. For several years, governance was competent, taxes were moderated, and executions were kept reassuringly rare. It was, by Roman standards, a promising start.

Governance and Political Style

Nero never showed much interest in administration. He delegated willingly, sometimes wisely, sometimes catastrophically. Where previous emperors cultivated senatorial goodwill, Nero drifted between indifference and open hostility. Senators soon realised that status offered no insulation from imperial suspicion.

Over time, paranoia replaced policy. Informers flourished. Treason trials multiplied. Executions became a tool not of statecraft but of emotional housekeeping. This was not unusual in Rome, but Nero practised it with a lack of restraint that unsettled even seasoned courtiers.

Yet it is worth noting that provincial governance remained largely stable. Rome’s machinery was robust enough to function even when the man at the top preferred rehearsals to reports.

Nero and the Arts

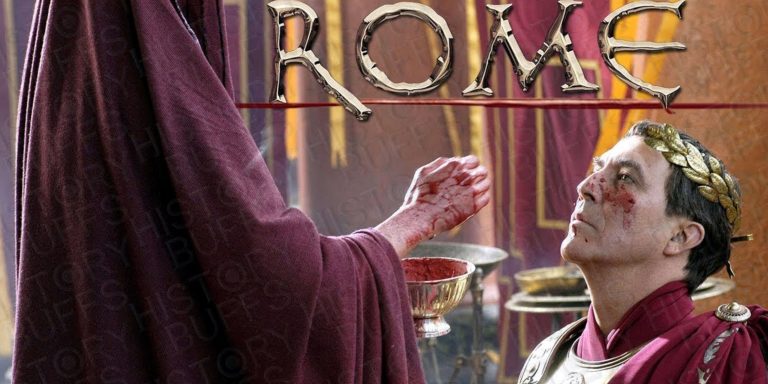

If Nero ruled reluctantly, he performed enthusiastically. He considered himself an artist first and an emperor second, which would have been eccentric in any society and alarming in Rome.

Nero sang, played the lyre, wrote poetry, and competed in Greek-style games. Attendance was not optional. Applause was mandatory. Leaving early was hazardous to one’s health. Roman elites found this deeply uncomfortable. An emperor was meant to embody gravitas, not demand encores.

Modern readers often mock this fixation, but it reveals something important. Nero wanted admiration on personal terms, not borrowed authority. He did not simply want power. He wanted to be loved for who he believed he was. History suggests this was not a realistic ambition.

The Great Fire of Rome

The fire of AD 64 defines Nero’s legacy more than any decree or performance. Large sections of Rome were destroyed, leaving tens of thousands homeless. Ancient sources disagree on whether Nero was responsible, but they agree on one thing. He handled the aftermath poorly.

Nero was not in Rome when the fire began and returned quickly to organise relief. This deserves acknowledgement. However, his decision to build the Domus Aurea, an enormous palace complex, on land cleared by the fire was politically disastrous. Even if innocent, he appeared guilty.

To redirect blame, Nero targeted Rome’s Christian community. The persecutions that followed were brutal and theatrical, fittingly enough, and ensured that Christian tradition would never forget his name. In this case, history’s grudge may be justified.

Military Affairs and Rebellion

Nero was not a soldier, and he knew it. Campaigns were left to generals, most of whom performed effectively. The eastern settlement with Parthia over Armenia was a genuine diplomatic success and avoided a costly war.

The real threat came from within. In AD 68, revolts in Gaul and Hispania exposed how shallow Nero’s support had become. When the Praetorian Guard withdrew loyalty, the game was up. Rome had many flaws, but it did not tolerate emperors who outlived their usefulness.

Death and Damnatio Memoriae

Nero fled Rome and, finding no allies willing to save him, took his own life. His reported last words lamented the loss of a great artist, which feels either tragically sincere or impressively tone deaf.

The Senate moved swiftly to erase him from official memory. Statues were destroyed. His name was removed from inscriptions. Yet this attempt failed in the long term. Nero survived in story, satire, and accusation. Few emperors achieved such enduring notoriety.

Legacy and Historical Judgement

Nero was neither the antichrist of legend nor a misunderstood reformer. He was an insecure autocrat with artistic ambitions unsuited to absolute power. His reign demonstrated how dangerous personal indulgence becomes when paired with unchecked authority.

At the same time, Rome did not collapse under him. The empire endured. Administration functioned. Provinces remained loyal longer than his reputation suggests. Nero’s failure was not incompetence alone but a refusal to understand what his position demanded.

History remembers Nero because he made himself unforgettable. That, at least, was an artistic success.

Seven Swords Takeaway

Nero forces historians into uncomfortable territory. He cannot be dismissed as pure caricature, nor defended as a victim of hostile sources alone. He was shaped by privilege, indulged by power, and undone by his own expectations of admiration.

If there is a lesson here, it is not about tyranny in the abstract. It is about the risks of confusing applause with authority. Rome learned it the hard way, and Nero paid the final price for the encore.