The Border Reivers lived in the long shadow between England and Scotland from the late medieval period into the early seventeenth century. They were not rebels in the modern sense, nor romantic outlaws in the way later folklore would insist. They were families shaped by a violent frontier, loyal to blood before crown, and practical to the point of ruthlessness. As a historian, I find them compelling precisely because they refuse neat moral boxes. Survival mattered more than law, and reputation mattered more than paperwork.

The world that created the Reivers

The Anglo Scottish border was unstable for generations. Authority thinned as it approached the frontier, and justice was uneven at best. When war flared, reiving was tolerated or even encouraged. When peace returned, the same men were suddenly criminals. This contradiction bred a culture that prized mobility, kinship, and retaliation.

Cattle were currency. Horses were lifelines. A good night ride could feed a family for months, while failure meant ruin. Tower houses dotted the landscape not as noble residences but as fortified statements that said, quietly and firmly, this ground is defended.

The Armstrongs, kings of Liddesdale

The Armstrongs dominated Liddesdale with a confidence that bordered on arrogance. Their numbers alone gave them power, but it was organisation that kept them feared. Raids were planned, scouts posted, escape routes rehearsed.

The most famous of them all was William Armstrong of Kinmont, better known as Kinmont Willie. His capture during a truce and dramatic rescue from Carlisle Castle became legend within his own lifetime. What fascinates me is not the jailbreak itself, but the message it sent. The Borders operated by their own rules, and even royal authority could be bent when kin and honour demanded it.

The Grahams, opportunists of the western March

The Grahams thrived on adaptability. Based largely on the western March, they shifted allegiance when it suited them and exploited the gaps left by inattentive wardens. English or Scottish mattered less than advantage.

Their reputation for treachery was earned, but also exaggerated by rivals. In truth, they were masters of the frontier economy, able to negotiate, intimidate, or raid depending on the moment. When James VI moved to pacify the Borders, it was the Grahams who were most ruthlessly dispersed, shipped to Ireland to break their power. That alone tells you how seriously they were taken.

The Elliots, fighters with a long memory

The Elliots were shaped by feud. Their conflicts with the Scotts and other neighbours stretched across decades, marked by ambushes, betrayals, and carefully remembered slights. To read Border records is to see how personal violence could be. Names recur. Grudges mature.

What strikes me about the Elliots is their endurance. They were not always the strongest family, but they were stubborn, adaptable, and deeply rooted. Even as royal pressure increased, they clung to their territory with a grim determination that feels almost modern.

The Nixons and Bells, specialists of the night ride

Lesser known than the Armstrongs or Grahams, the Nixons and Bells nonetheless embodied the reiver ideal. Lightly equipped, well mounted, and deeply familiar with the land, they excelled at fast raids and quicker escapes.

Their names appear again and again in court records, not because they were careless, but because the system was overloaded. Justice on the Border was a blunt instrument. Many were hanged, many more pardoned, and some managed to grow old, which may be the rarest achievement of all in reiver society.

Charltons, the shadow over Tynedale

The Charltons held sway in North Tynedale, often clashing with both English authorities and neighbouring families. They built power through intimidation and strongholds rather than sheer numbers. Their story reminds us that reiving was not confined to Scotland. English families were just as deeply embedded in the culture of raid and reprisal.

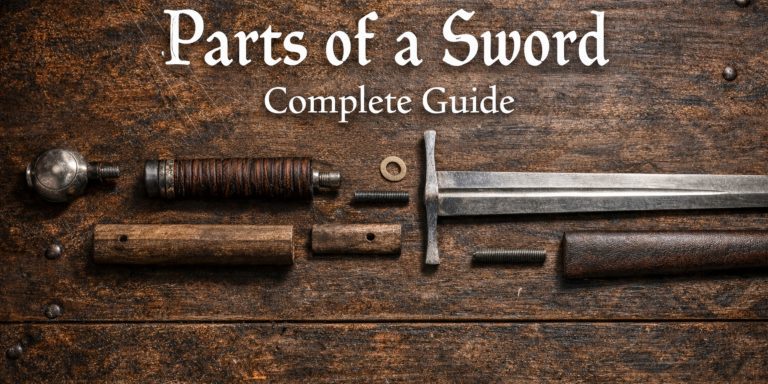

Arms, horses, and practical violence

Reivers fought as they lived, efficiently. Spears and lances were common, suited to horseback fighting and pursuit. Swords were practical rather than ornate, often single edged and built for use rather than display. Armour was light, if worn at all, favouring speed over protection.

The horse mattered most. A good reiver horse could cross broken ground in darkness and still outrun pursuit. Many raids succeeded or failed on the quality of the mount rather than the blade.

Decline and suppression

The end came not with a single battle but with administration. When James VI of Scotland became James I of England, the border lost its political usefulness. The Middle Shires were pacified through executions, transportation, and relentless legal pressure.

As a historian, I find this ending oddly unsatisfying. The Reivers did not vanish. They adapted, emigrated, or faded into farming families whose ancestors once terrified entire valleys. Their world ended because it no longer served the state, not because it lacked its own logic.

The Seven Swords Takeaway

The Border Reivers challenge comfortable narratives about law and order. They remind us that morality is often shaped by environment, and that violence can be normalised when authority fails. They were not heroes, but they were not monsters either. They were products of a hard land and a harder political reality.

When I walk the Borders today, past ruined towers and quiet rivers, it is easy to forget how loud this landscape once was with hoofbeats and alarm bells. The stones remember, even if we choose not to.

Watch the documentary: