Horatio Hornblower feels like fiction until you realise how little of it actually is. The duels, the storms, the brutal discipline, the constant anxiety about promotion and pay, all of that comes straight out of the real Napoleonic Wars at sea. C. S. Forester did not invent a fantasy navy. He polished a very sharp, very uncomfortable reality.

What follows is the real historical world Hornblower is sailing through, stripped of romance where needed and backed by the kind of detail the Royal Navy lived with every day.

Britain at War With Everyone Important

By the time Hornblower is a midshipman, Britain has been fighting France on and off for a decade. After 1803, it becomes a full commitment. Napoleon controls most of Europe. Britain controls the sea, or at least tries very hard to.

This imbalance explains almost everything in the series. Britain cannot defeat France on land, so the navy becomes the main weapon. Blockades are not glamorous, but they are how empires suffocate. Hornblower spends months staring at empty horizons because that is exactly what the Royal Navy did. Victory came from patience, not fireworks.

The war also never really pauses. Ships rotate crews, not missions. Officers age at sea. Promotions come slowly, if at all. Forester captures that grinding persistence perfectly.

The Royal Navy Hornblower Actually Served In

Hornblower’s navy is not a gentleman’s club. It is a floating industrial machine powered by fear, hierarchy, and salt beef.

Discipline is relentless. Flogging is routine. Courts martial hover over every decision. A captain who hesitates risks not just defeat, but disgrace. Hornblower’s constant self doubt is not neurosis, it is survival instinct.

Social class matters, but competence matters more. The navy is one of the few places in Georgian Britain where merit can, occasionally, outrun birth. Hornblower’s awkward rise mirrors real officers like Thomas Cochrane and Edward Pellew, men who annoyed their superiors but kept winning battles.

Life Aboard Ship Was Genuinely Miserable

Hornblower is often wet, hungry, exhausted, and mildly traumatised. This is not narrative flavour. This is accuracy.

Ships stink. Food is monotonous and often rotten. Fresh water goes green after weeks in barrels. Scurvy looms constantly. Sleep comes in short, broken bursts between watches. Privacy does not exist.

Forester does not exaggerate Hornblower’s isolation. Even surrounded by hundreds of men, an officer is alone with his decisions. That quiet dread before battle, where Hornblower obsesses over tiny details, is straight from real naval journals.

Naval Warfare Was Brutal and Intimate

Forget cinematic broadsides fired from polite distances. Naval combat in the Napoleonic era is close, loud, and personal.

Ships aim to smash rigging, cripple movement, then rake the enemy with cannon fire that turns decks into butcher’s floors. Boarding actions follow, which are chaotic knife fights on rolling planks slick with blood.

Hornblower’s tactical brilliance often lies in restraint. He avoids battle when he should, and commits fully when escape is gone. That mindset reflects the real Royal Navy, which prized decisiveness but punished recklessness.

Nelson’s Shadow Is Everywhere

Horatio Hornblower is not Horatio Nelson, but he lives in Nelson’s world.

Nelson defines naval warfare during this period. Aggressive tactics, breaking enemy lines, trusting captains to act independently, all of this filters down to men like Hornblower. The expectation is initiative, not obedience.

Hornblower’s fear of command fits this perfectly. Nelson wanted captains who could think for themselves. That freedom came with terrifying responsibility. Make the wrong call, and there is no one to hide behind.

The Enemy Was Not Incompetent

French and Spanish officers in Hornblower are dangerous, clever, and professional. This matches reality.

British naval dominance is not guaranteed. It is earned through constant drilling, better gunnery, and ruthless blockades. Many British victories come down to marginal advantages exploited well, not overwhelming superiority.

Hornblower’s respect for his enemies feels modern because it is. Forester understood that victory means nothing if your opponent is a caricature.

Prize Money, Promotion, and Anxiety

One of Hornblower’s least heroic motivations is money. This is also one of the most realistic.

Officers rely on prize money to survive. Capture an enemy ship, and your financial future changes overnight. Miss that chance, and you stay poor. Promotions are slow, political, and often arbitrary.

Hornblower’s obsession with rank and security is not ambition, it is maths. Without promotion, he cannot marry, retire, or breathe easily. Many real officers shared that quiet panic.

Why Hornblower Still Works

Hornblower endures because it refuses to pretend the Napoleonic Wars were tidy or noble. They were exhausting, morally complicated, and emotionally draining.

Forester gives us a hero who wins battles but loses sleep. A man who commands decisively and doubts relentlessly. That balance feels honest, even now.

If Hornblower sometimes seems anxious or socially awkward, that is because he belongs to a world where a single misjudgement can end careers, crews, and lives. Confidence would be unrealistic. Care would be irresponsible.

Final Thoughts From the Quarterdeck

Hornblower is not escapism. It is controlled exposure to a historical pressure cooker.

The Napoleonic Wars at sea were defined by waiting, fear, sudden violence, and long stretches of nothing at all. Forester captured that rhythm with unsettling accuracy. The result is a series that feels grounded even when it is dramatic.

If you ever wondered why Hornblower looks permanently stressed, the answer is simple. Anyone sane in his position would be.

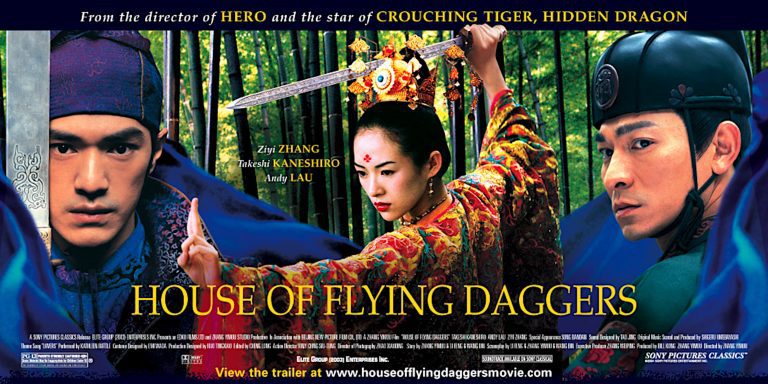

Watch a clip from the series: