Baldwin I of Constantinople was never meant to be emperor of anything, least of all Constantinople. Born Baldwin IX of Flanders, he set out on the Fourth Crusade as a conventional high medieval prince. What he became instead was the first ruler of the short lived and deeply unstable Latin Empire, crowned in Hagia Sophia in 1204 after the sack of the greatest Christian city in the east.

As a historian, I find Baldwin endlessly fascinating because his reign captures a moment when western ambition collided with eastern reality and lost. His rule was brief, his resources thin, and his enemies numerous. Yet he was not incompetent, nor reckless in the usual crusader sense. His failure tells us more about the limits of crusader power than about personal weakness.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Baldwin was born in 1172 into the comital house of Flanders and Hainaut, one of the wealthiest and most militarised regions of northern Europe. By the late twelfth century, Flanders produced hardened nobles used to campaigning, castle warfare, and complex feudal politics.

He took the cross in 1199, alongside figures such as Boniface of Montferrat. The Fourth Crusade’s diversion first to Zara and then to Constantinople reshaped Baldwin’s destiny. When the city fell in April 1204, the crusader leadership faced an awkward problem: someone had to rule it.

Boniface expected the throne. Instead, Baldwin was elected emperor by a council of crusader barons and Venetian representatives. He was seen as pious, politically safe, and less likely to dominate Venetian interests. In other words, he was acceptable to everyone, which in medieval politics is rarely a good sign.

Coronation and Rule of the Latin Empire

Baldwin was crowned emperor in May 1204 in Hagia Sophia, adopting the title of Emperor of Constantinople. The new Latin Empire, formally known as the Latin Empire, was imperial in name only.

Its problems were immediate and structural:

- Constantinople itself was damaged, depopulated, and hostile.

- Byzantine successor states emerged at Nicaea, Epirus, and Trebizond.

- Bulgaria under Tsar Kaloyan was aggressive and opportunistic.

- The empire lacked manpower, money, and legitimacy.

Baldwin attempted to impose western feudal structures onto a deeply Byzantine landscape. Latin barons received fiefs, Venetian interests were entrenched, and Greek elites were marginalised. From a governance perspective, this was understandable but disastrous. The empire became overstretched before it had properly begun.

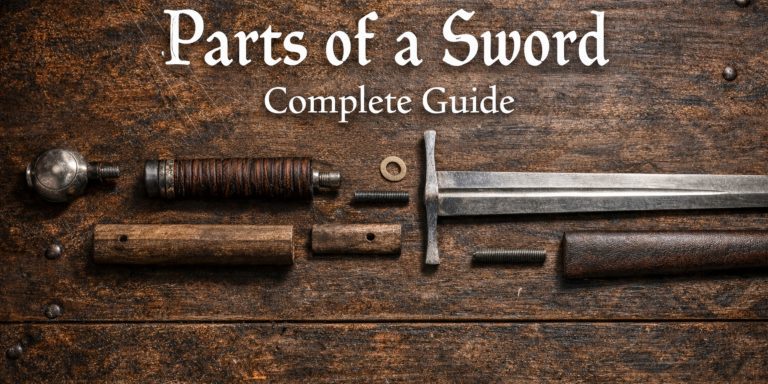

Arms and Armour

Baldwin fought as a high medieval western knight, equipped in the fashion of the early thirteenth century rather than adapting to Byzantine or Balkan styles.

Typical equipment likely included:

- A mail hauberk with coif, knee length or longer

- Reinforced mail chausses for the legs

- A conical or early flat topped helmet, sometimes with a nasal

- A kite or early heater shield bearing Flemish heraldry

- A straight, double edged arming sword

- A heavy cavalry lance for mounted combat

There is no evidence that Baldwin adopted Greek lamellar armour or steppe influenced gear, unlike some later Latin rulers in the region. This mattered. Against Bulgarian forces using light cavalry, ambush tactics, and terrain mastery, western heavy cavalry lost much of its advantage.

As a commander, Baldwin seems to have trusted traditional knightly shock tactics in situations where they were ill suited.

Battles and Military Acumen

Baldwin’s military career as emperor was short and brutal. His most important campaign was also his last.

Conflict with Bulgaria

In 1205, Baldwin moved against Tsar Kaloyan of Bulgaria, who had aligned himself with disaffected Byzantine Greeks. The confrontation culminated at the Battle of Adrianople.

This battle was a textbook disaster:

- Latin forces advanced aggressively without adequate reconnaissance.

- Bulgarian troops used feigned retreats and ambush tactics.

- Latin knights were drawn into broken ground.

- Heavy cavalry formations collapsed under sustained harassment.

Baldwin was captured during the rout. His army disintegrated, and with it the illusion that the Latin Empire could dominate the Balkans militarily.

As a historian, I hesitate to call this incompetence. Western armies repeatedly fell victim to steppe and Balkan tactics during this period. Baldwin’s mistake was strategic confidence rather than tactical ignorance. He underestimated an enemy who understood terrain and asymmetric warfare far better than he did.

Captivity and Death

Baldwin was taken to the Bulgarian capital of Tarnovo. His fate remains murky, but most sources agree he died in captivity in 1205, possibly executed after being accused of conspiracy or mistreatment of Kaloyan’s envoys.

Later legend claims his skull was turned into a drinking cup. This is likely propaganda, but it reflects how completely his authority collapsed in the eyes of his enemies.

His brother Henry succeeded him and proved a more capable ruler, which only sharpens the tragedy of Baldwin’s short reign.

Artefacts and Material Legacy

No personal arms or armour definitively linked to Baldwin survive. However, material culture from his reign does exist.

You can see related artefacts in:

- The Treasury of San Marco in Venice, which holds numerous objects taken from Constantinople in 1204

- The Istanbul Archaeological Museums, where late Byzantine and early Latin period artefacts contextualise his reign

- The Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, which display material tied to Flemish crusading culture

Seals and coinage from the early Latin Empire period survive in fragmentary form, showing attempts to merge western imperial titles with Byzantine iconography. These objects quietly reveal how uncertain Latin authority really was.

Archaeology and Recent Findings

Recent archaeological work in Istanbul continues to reshape our understanding of the Fourth Crusade’s aftermath rather than Baldwin personally.

Key developments include:

- Urban archaeology revealing levels of destruction and abandonment dating to the early thirteenth century

- Reassessment of Latin era fortifications along Constantinople’s land walls

- Numismatic studies clarifying the economic collapse following 1204

What emerges is a city struggling to function, let alone serve as the capital of a new empire. Baldwin ruled an idea more than a state, and archaeology increasingly confirms that reality.

Historical Reputation and Assessment

Baldwin I of Constantinople is not a villain, nor a hero. He was a capable northern European noble placed in an impossible situation and asked to rule a city that rejected him, defend borders he could not hold, and legitimise a conquest that fractured Christendom.

From a historian’s perspective, his reign matters precisely because it failed. It marks the point where crusading ambition outran political and military reality. Baldwin did not lack courage or faith. He lacked time, resources, and an empire willing to exist.

Sometimes history is less about great men shaping events and more about watching events quietly grind them down.