A historian cannot help feeling a certain admiration for the sheer audacity behind the rise of the Aztec Triple Alliance. Three city states, once jostling for scraps along the shores of Lake Texcoco, forged a political creation that reshaped Central Mexico. The Alliance was not a harmonious brotherhood, yet its internal tensions did little to blunt its capacity for conquest. What emerged was a system that balanced ambition with ritual order, wealth with obligation, and power with the ever present threat of upheaval.

Origins and Formation

The Alliance began in 1428 when Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan united against the Tepanec empire of Azcapotzalco. Tenochtitlan had sat under Tepanec pressure for years, and one can almost sense the relief in the historical accounts once the tables finally turned. Texcoco, dispossessed and eager to reclaim prestige, offered intellectual and military leadership. Tlacopan, caught between the region’s great predators, joined the alliance as a prudent act of survival.

This was not simply a military pact. It was a recalibration of power in the Basin of Mexico that allowed these cities to carve up tribute and influence while presenting a united front to neighbouring polities.

Structure of the Alliance

At its core the Alliance divided the spoils of war in a ratio that reflected each partner’s standing. Tenochtitlan took the largest share, Texcoco followed, and Tlacopan received the smallest. Such an arrangement did not mask the reality that Tenochtitlan, by the late fifteenth century, dominated the enterprise. The Mexica tlatoani became the foremost political figure in the region, although Texcoco’s rulers maintained a reputation for scholarship and law that gave them influence of a different kind.

In practice, each member retained autonomy over internal matters. Tribute routes, however, were the lifeblood of the system and required shared military enforcement. If one city wished to launch a campaign, the others were expected to commit troops or at least refrain from obstruction. It was a diplomatic dance that often required more subtlety than surviving sources reveal.

Expansion and Military Power

The Alliance grew rapidly through the fifteenth century. Cities such as Tlaxcala resisted fiercely, but many others folded under the pressure of combined armies. Tribute lists reveal a bewildering array of goods flowing into the capitals, from cotton and cacao to feathers and metalwork. For a historian, the sheer organisational strength required to keep these networks functioning is almost more impressive than the battlefield victories.

The Mexica warrior ethos became the public face of the Alliance’s expansion, but this masks the crucial administrative and logistical work performed by subordinate towns. Without these tributary systems the Aztec state would have been a very lean and ill equipped creature indeed.

Religion and Ideology

Religion buttressed the state with a seriousness that is difficult for modern readers to grasp. The alliance’s campaigns were framed as necessary acts to maintain cosmic order, and the capture of prisoners for sacrifice formed part of this logic. The temples of Tenochtitlan stood as physical reminders that ritual and statecraft were inseparable.

Each city state maintained its own deities, yet the cults associated with Tenochtitlan rose to particular prominence. Huitzilopochtli’s role in guiding the Mexica migration narrative became a useful political tool, grounding Tenochtitlan’s authority in sacred history.

Life Within the Alliance

Daily life for common people did not revolve around imperial politics, though its effects were unmistakable. Tribute obligations, military levies and occasional festivals shaped ordinary rhythms. Markets thrived on the movement of goods along the Alliance’s networks. Poets, craftsmen and nobles benefited immensely from the concentration of wealth.

As a historian reading these traces, one senses both the vibrancy and the strain. Success enriched the centres of power, yet it required constant enforcement along the periphery. Rebellion was an ever present concern, never entirely snuffed out.

Challenges and Internal Tensions

The Alliance was remarkably durable, but not immune to friction. Texcoco’s rulers occasionally bristled at Tenochtitlan’s growing dominance, and Tlacopan’s influence dwindled so sharply that one almost feels sympathy for its sidelined nobility. Succession disputes, diplomatic quarrels and the familiar temptations of imperial overreach all gnawed at the system.

Had the Spanish not arrived when they did, it is tempting to speculate whether the Alliance would have fractured under its own weight or recalibrated once again. Historians are cautious about such speculation, but the question lingers.

The Spanish Invasion and Collapse

The arrival of Hernán Cortés in 1519 exploited long standing tensions between the Alliance powers and their subject states. Indigenous allies proved decisive in dismantling the imperial structure. Tenochtitlan’s fall in 1521 marks the end of the Alliance as a functioning political order.

The collapse was not merely military. It was a crisis of confidence, logistics and disease. Tribute systems failed, leadership fractured and the spiritual foundations of the empire were challenged by upheaval.

Legacy

The Aztec Triple Alliance remains one of the most sophisticated pre Columbian political systems, balancing military ferocity with cultural creativity. Its legacy endures through archaeological remains, codices and the living traditions of descendant communities across Mexico.

As a historian, one cannot escape the sense that the Alliance was a world still in motion when it was struck down. It had not exhausted its potential. Its roads, markets and temples may have crumbled, but the ideas that sustained it remain woven into the history of Mexico.

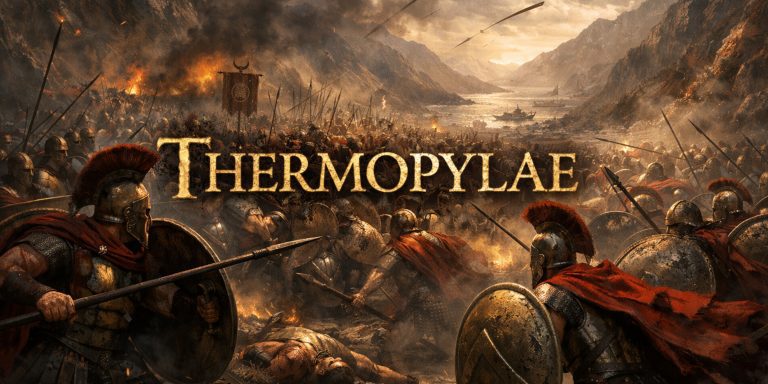

Watch the documentary: