Few figures in Roman history inspire such admiration and regret as Germanicus Julius Caesar. Born in 15 BC, the adopted son of Tiberius and father of Caligula, Germanicus embodied the ideal Roman commander: courageous, charismatic, and adored by both his troops and the populace. His life seemed destined for the purple, yet his sudden death in 19 AD in the East left Rome mourning a man who could have been one of its greatest emperors.

His career sits at the pivot of early imperial Rome, a time when the Republic’s military traditions still echoed through legions that were growing used to serving emperors rather than the Senate. Germanicus was the last great general who felt both republican and imperial at heart.

Arms and Armour

Germanicus’ campaigns took him deep into the forests of Germania and across the eastern provinces, demanding flexibility in armour and weapons.

Typical Equipment of a Roman Commander (Early 1st Century AD):

| Item | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Helmet (Galea) | Bronze or iron with ornate plume crest | High-ranking officers often had embossed decoration, likely featuring laurel motifs. |

| Body Armour (Lorica Segmentata or Hamata) | Segmentata emerging in his era, though chainmail (hamata) remained common | Germanicus probably wore hamata for mobility in forest terrain. |

| Sword (Gladius Hispaniensis) | Standard short sword used for thrusting | Elegant versions with inlaid silver have been found in legionary sites along the Rhine. |

| Shield (Scutum) | Curved, rectangular shield with central boss | Officers often bore gilded designs or symbols of their legions. |

| Command Baton (Vitis) | Symbol of authority among senior officers | Likely ivory or decorated wood in his case. |

One can imagine him on campaign, his mail glinting under a rain-soaked sky, surrounded by veterans hardened from Varus’ defeat, all eager to reclaim honour in the Teutoburg Forest.

Battles and Military Acumen

Germanicus’ military record is not lengthy, but it is glittering. His campaigns in Germania between 14 and 16 AD restored Roman confidence after the Varian disaster and nearly reversed the loss of the three legions annihilated by Arminius.

Campaigns in Germania (14–16 AD)

- Battle of Idistaviso (16 AD):

Germanicus led a coordinated assault against Arminius’ coalition near the Weser River. His use of combined infantry and cavalry tactics reflected both discipline and adaptability. Tacitus describes the clash as brutal and personal, with Germanicus himself rallying the line and dedicating captured spoils to Mars and Jupiter. - Recovery of the Eagle Standards:

Few deeds meant more to Roman pride. Germanicus retrieved two of the three lost legionary eagles from the Teutoburg disaster. Symbolically, it erased part of Rome’s greatest humiliation of the early Empire. - Naval Operations in the North:

He innovated by deploying a massive fleet to transport and supply legions, navigating the unpredictable Germanic rivers and North Sea. The expedition ended with severe storms, yet it demonstrated logistical mastery ahead of its time.

Eastern Campaign (17–19 AD)

Dispatched to the East to restore order and negotiate client kingships, Germanicus displayed political tact and restraint. His visit to Egypt without imperial consent, however, enraged Tiberius, who saw it as overreach.

In Syria, he clashed with the governor Gnaeus Piso, whose hostility culminated in Germanicus’ mysterious death. Poison was suspected, though never proved. The Senate’s public mourning suggests that even they viewed him as the empire’s moral centre.

Military Reputation

Tacitus paints Germanicus as both warrior and scholar: generous, eloquent, and humane. He addressed his troops by name, shared their hardships, and never sought cruelty for its own sake. His campaigns showed him to be tactically sound, not merely brave.

What strikes me, reading Tacitus and Suetonius, is that Germanicus seemed too noble for the Tiberian age. His honour, charisma, and popularity made him dangerous to the cautious and jealous emperor who adopted him. The tragedy of Germanicus is not his death, but how it altered Rome’s course.

Where to See Artefacts

Although few personal belongings survive, many artefacts from his era provide a tangible sense of his world.

| Location | Artefacts | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Römisch-Germanisches Museum (Cologne) | Weapons, armour fragments, and military equipment from the Rhine frontier | Represents the very legions under Germanicus’ command. |

| British Museum (London) | Bronze statuettes and military decorations from the early Julio-Claudian period | Several pieces depict idealised commanders possibly modelled on Germanicus. |

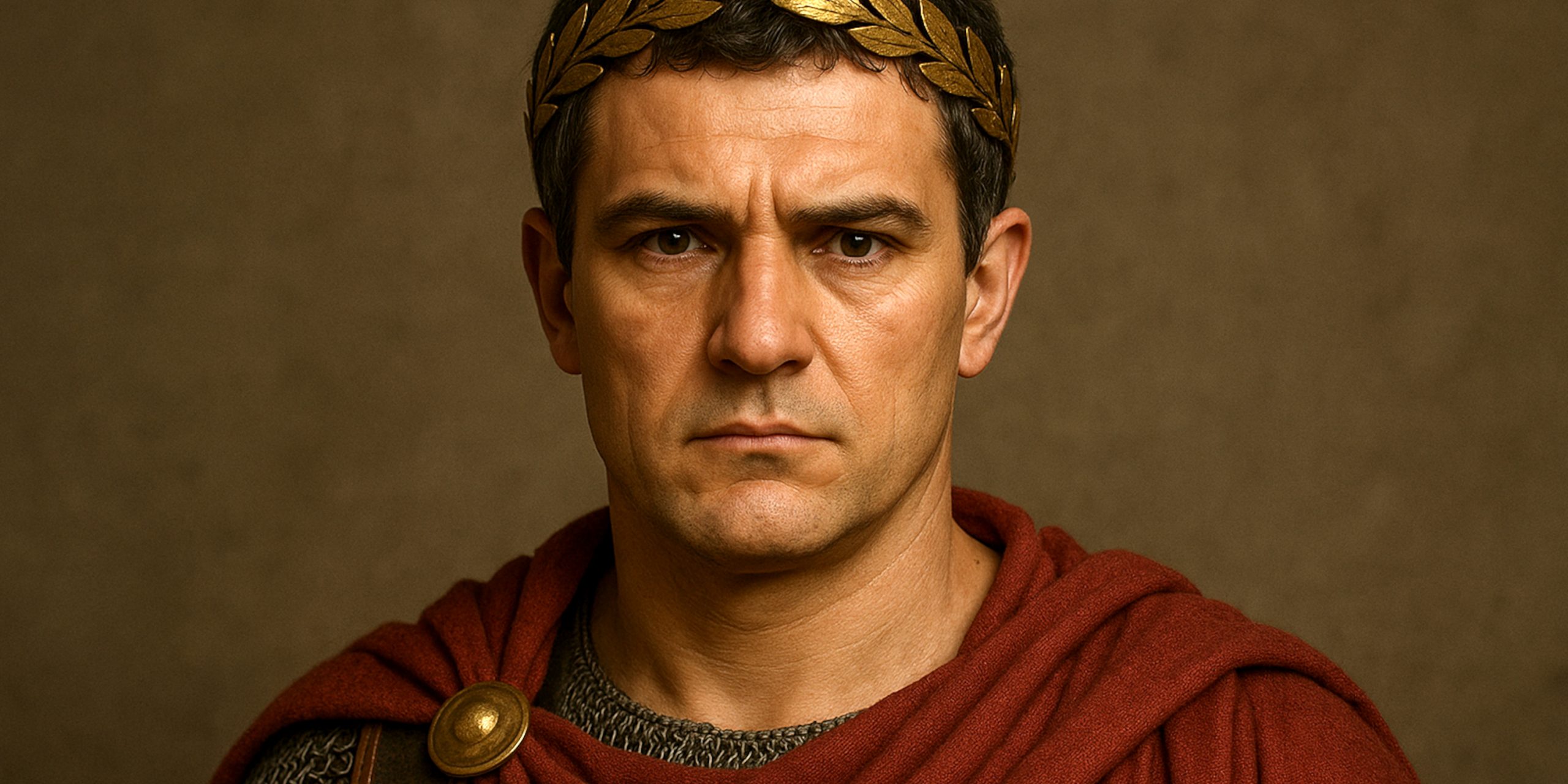

| Museo Nazionale Romano (Rome) | Busts and inscriptions dedicated to Germanicus | The marble portraits show a young man with the stern grace of Augustus. |

| Museum of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (Kalkriese) | Battlefield finds: pilum heads, gladii, and Roman coins | A direct link to the campaigns Germanicus led to avenge Varus. |

Latest Archaeological Findings

Recent excavations in Kalkriese continue to reveal new evidence of Roman troop movements and Germanic counterattacks. Finds of Roman marching camps east of the Rhine suggest the depth of Germanicus’ penetration into enemy territory, once thought implausible.

In Antioch, where he died, ongoing digs around the ancient Orontes River valley have unearthed Julio-Claudian villas and inscriptions linked to the provincial administration of his time. Though none name Germanicus directly, they provide valuable context for the politics surrounding his final months.

Satellite analysis of ancient river routes in northern Germany also gives credence to the accounts of his naval operations, showing that such fleet movements were logistically possible even in those difficult waterways.

Legacy

Germanicus’ death in 19 AD left a vacuum. His popularity with the legions and people had been immense, his reputation spotless. The Senate’s unprecedented mourning and the shrines erected in his name across the empire speak volumes about what he represented: the lost promise of a benevolent, just ruler.

His son, Caligula, inherited his name but not his virtues. The Roman populace would long remember Germanicus as the emperor they never had. To me, studying his campaigns and reading the words of those who served him, it is clear that he personified the final echo of Rome’s republican virtue wrapped in imperial glory.

Seven Swords Takeaway

Germanicus stands as one of history’s great “what-ifs”. His life bridges the gap between the principled ideal of Augustus’ Rome and the darker intrigues of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. He was not just a soldier, but a symbol of what leadership could have been: courageous yet kind, brilliant yet restrained.

When I look at his statues in Rome, I can’t help but wonder how different the empire’s story might have been if Germanicus had lived. The marble is cold now, but it still carries the faint warmth of a man Rome loved too much to forget.

Watch the documentary: