What Spartacus Was Really Trying to Be

When Spartacus landed in 2010, it looked like cheap provocation. Slow motion blood sprays, dialogue that sounded like it had been lifted from a gladiator-themed metal album, and enough stylised violence to make Rome feel like a fever dream.

Then something unexpected happened. Beneath the excess was a surprisingly disciplined story about power, slavery, ambition, and survival. It was lurid on the surface and oddly serious underneath. Think exploitation cinema wearing a history degree it occasionally bothered to read.

The show never pretended to be a documentary. What it did instead was far more interesting. It used Roman brutality as a language, not a gimmick.

The Historical Spartacus, and Why the Show Bent the Truth

The real Spartacus was a Thracian auxiliary soldier turned enslaved gladiator who led the Third Servile War from 73 to 71 BC. Ancient sources like Plutarch and Appian paint him as clever, disciplined, and far more strategic than Roman elites were comfortable admitting.

The show leans into this but sharpens the edges. Spartacus becomes a moral centre in a world designed to grind morality out of people. Historically, the rebel army was not a band of noble freedom fighters. It was a volatile coalition of escaped slaves, bandits, and opportunists. The series simplifies this for clarity, but it keeps the chaos. Leadership is never stable. Loyalty is always conditional.

That part is actually accurate.

Blood and Sand

Spartacus: Blood and Sand is where the franchise earns its reputation. The Capuan ludus of Batiatus is a pressure cooker. Gladiators are assets. Slaves are disposable. Honour exists only when it is profitable.

The violence is theatrical, but the social structure is brutally real. Roman gladiatorial schools were financial enterprises backed by elite patrons. Death in the arena was expensive, not casual. The show exaggerates the bloodshed but nails the economics. A fighter like Spartacus was valuable, which is why his rebellion cuts so deeply. He was not meant to be thrown away.

Gods of the Arena

The prequel, Spartacus: Gods of the Arena, is quietly one of the smartest parts of the franchise. It trades spectacle for politics and is better for it.

This is Rome at its most cynical. Ambition matters more than loyalty. Reputation is currency. Watching Batiatus claw his way up Capuan society feels closer to real Roman patronage networks than anything in Blood and Sand. The violence is still there, but it feels purposeful rather than indulgent.

Also, it makes later betrayals hurt more, which is a neat trick.

Vengeance and War of the Damned

After Andy Whitfield’s death, the series could have collapsed. Instead, Spartacus: Vengeance pivots hard into guerrilla warfare, followed by Spartacus: War of the Damned, which turns the rebellion into a full-scale insurgency.

Historically, this mirrors the real war surprisingly well. Spartacus defeated multiple Roman armies not through brute force but by exploiting arrogance and poor coordination. The show captures that escalation. Rome only takes the threat seriously when Crassus enters the picture, which again tracks the sources.

It also shows the cost of rebellion. Freedom does not come cleanly. It comes with fracture, betrayal, and exhaustion.

The Characters That Made It Stick

Spartacus is the heart, but the franchise thrives on its supporting cast. Characters like Batiatus, Lucretia, Crixus, and Ashur work because they are not heroes. They are survivors.

Ashur in particular stands out. Historically inspired by the kind of informers and climbers that thrived in Roman society, he is slippery, resentful, clever, and painfully aware of his own weakness. Rome was full of men like him. They just did not usually get this much screen time.

Which brings us neatly to the spin-off.

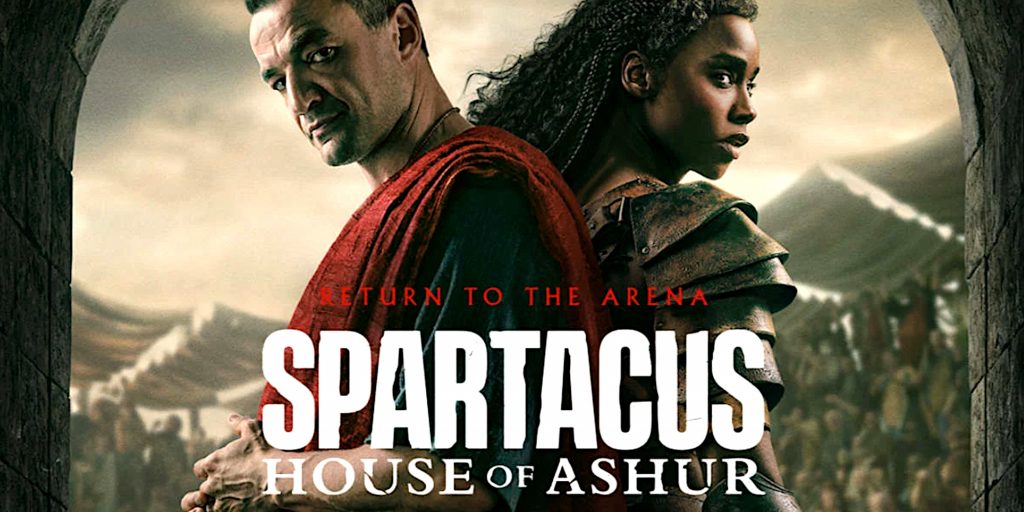

House of Ashur, A Dangerous New Angle

House of Ashur was an inspired choice. Instead of another rebellion story, it zooms in on survival inside the Roman system.

Ashur was never a warrior who could win outright. He was a negotiator, a snitch, a political animal. A series centred on him promises something closer to Roman intrigue than battlefield heroics.

From a historical perspective, this is fertile ground. Most people in the Roman world did not rebel. They adapted. Ashur represents that uncomfortable truth.

Production Overview

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Creators | Steven S. DeKnight, Sam Raimi, and Robert Tapert |

| Key Influences | Inspired by the 1960 Kubrick film Spartacus and the graphic novel 300 |

| Filming Location | Shot entirely in New Zealand with heavy use of CGI for stylised backdrops |

| Budget | High-budget production, noted for lavish costumes and slow-motion fight choreography |

| Challenges | Lead actor Andy Whitfield’s tragic death after Season 1 led to a prequel (Gods of the Arena) and recasting with Liam McIntyre |

Main Cast

| Actor | Role | Key Traits |

|---|---|---|

| Andy Whitfield | Spartacus (Season 1) | Thracian gladiator turned revolutionary leader; praised for emotional depth |

| Liam McIntyre | Spartacus (Seasons 2–3) | Took over post-Whitfield; portrayed Spartacus’ evolution into a tactical leader |

| Lucy Lawless | Lucretia | Scheming wife of Batiatus; manipulative and morally ambiguous |

| John Hannah | Quintus Batiatus | Ambitious lanista (gladiator owner); a blend of humour and villainy |

| Manu Bennett | Crixus | Gaulish gladiator; evolves from rival to Spartacus’ loyal ally |

| Peter Mensah | Oenomaus (Doctore) | Mentor figure; embodies honour amidst brutality |

| Viva Bianca | Ilithyia | Roman noblewoman; manipulative and central to political subplots |

Series Breakdown

| Season | Title | Key Events | Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (2010) | Blood and Sand | Spartacus’ enslavement, rise as a gladiator, and rebellion against Batiatus | Betrayal, survival, and identity |

| Prequel (2011) | Gods of the Arena | Focuses on Batiatus’ rise and Gannicus’ glory days pre-Spartacus | Ambition and corruption in Capua |

| 2 (2012) | Vengeance | Spartacus’ rebellion gains momentum; clashes with Roman general Glaber | Leadership struggles and moral complexity |

| 3 (2013) | War of the Damned | Final showdown with Rome; explores the cost of freedom | Sacrifice and the limits of rebellion |

Weaponry and Combat

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Stylised Violence | Over-the-top gore and slow-motion combat; criticised as gratuitous but central to the tone |

| Key Weapons | Gladius (Roman short sword), spears, tridents; historically inspired but exaggerated for drama |

| Fight Choreography | Praised for intensity; blends gladiatorial techniques with cinematic flair |

| Symbolism | Weapons represent power (e.g., Spartacus’ sword) and oppression (Roman armour) |

Critical Reception

| Aspect | Praise | Criticism |

|---|---|---|

| Storytelling | Bold narrative with intricate political scheming | Over-reliance on tropes like the “chosen one” |

| Characters | Complex arcs, especially Batiatus and Lucretia | Female characters often reduced to archetypes |

| Visual Style | Striking use of colour and CGI; compared to 300 | Low-budget CGI in early episodes |

| Legacy | Influenced later shows like Game of Thrones; revived interest in gladiator epics | Excessive nudity and violence alienated some viewers |

Notable Quotes

- Spartacus: “I am Spartacus!” (A rallying cry against tyranny)

- Lucretia: “All men must be broken to serve Rome.”

- Batiatus: “Jupiter’s cock! Must I do everything myself?” (A fan-favourite expletive)

Realism vs. Artistic Licence

- Historical Accuracy: Loosely based on Spartacus’ 73–71 BCE rebellion; takes liberties for drama (e.g., gladiators rarely fought to the death)

- Themes: Explores slavery’s dehumanising effects and the moral decay of Rome

Where to Watch

| Platform | Availability |

|---|---|

| Streaming | Starz, Amazon Prime Video (region-dependent) |

| Physical Media | DVD/Blu-ray box sets available |

A decade on, Spartacus remains oddly relevant. Not because of the blood or the shock value, but because it understands power. Rome is not evil because it is violent. It is violent because it is organised to be.

The show gets that systems matter more than villains. Kill one master and another takes his place. The rebellion was doomed historically, and the series never fully lets you forget that. Freedom is possible, but it is never free.

Also, it is still wildly entertaining, which helps.

Watch the trailer: