Swords look simple until you start paying attention. Then you realise every curve, ridge, and lump of metal has a name, a reason for existing, and usually a long argument attached to it. Knowing the parts of a sword is not just trivia. It helps you understand how a weapon was meant to be used, why it handles the way it does, and whether that suspiciously cheap “medieval sword” online should be avoided at all costs.

This guide breaks down every major component of a sword in clear terms. No mysticism, no fantasy nonsense, just what things are, where they sit, and why they matter.

Blade

Blade Overview

The blade is the working heart of the sword. Everything else exists to support it, control it, or stop it from harming the person holding it.

Key things the blade determines:

- Cutting versus thrusting ability

- Weight distribution and balance

- Durability under stress

- Cultural and period identity

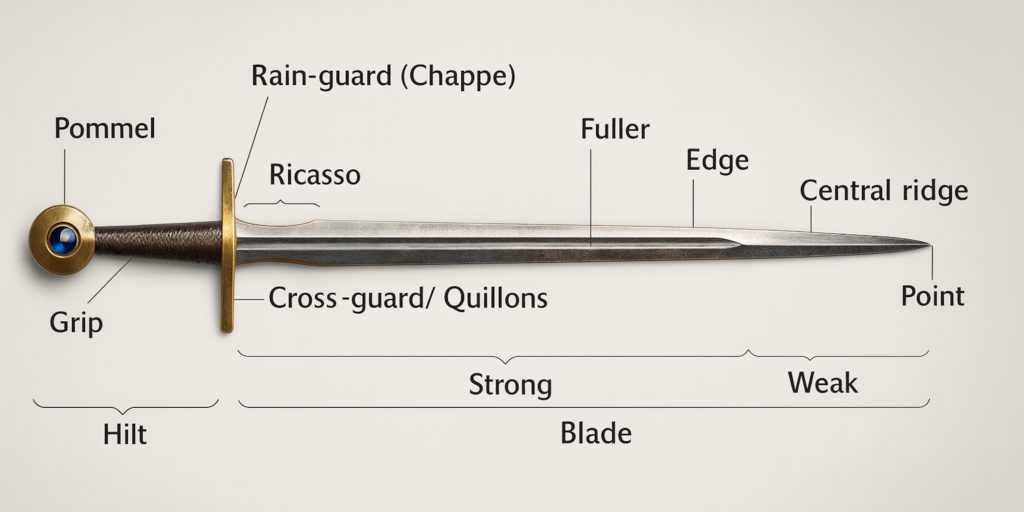

Edge

The edge is the sharpened portion of the blade, designed to cut.

Common variations include:

- Single edge, typical of sabres and falchions

- Double edge, common on arming swords and longswords

- Partially sharpened edges, often seen on later military swords

Edge geometry affects how a sword cuts far more than sharpness alone. A thin, acute edge bites easily but chips faster. A thicker edge sacrifices slicing power for longevity.

Tip or Point

The tip is where thrusting happens, whether the sword was designed for it or not.

Broadly speaking:

- Narrow, reinforced points excel at piercing mail and gaps in armour

- Wider tips favour cutting and draw cuts

- Some blades balance both, especially later medieval designs

A broken or poorly shaped tip is usually a red flag on antiques and reproductions alike.

Fuller

The fuller is the groove or channel running along the blade.

Despite popular myths, it does not make the blade “lighter by hollowing it out like a straw”. Its real purposes are:

- Reducing weight without losing stiffness

- Improving balance

- Controlling flex during impact

Not all swords have fullers, and some have several. Their presence often signals a design focused on efficient handling rather than brute force.

Ricasso

The ricasso is the unsharpened section of blade just above the guard.

You mostly see it on:

- Rapiers

- Complex-hilted swords

- Some late medieval longswords

It allows finger placement for added control and safer handling during close work. If you see finger rings nearby, the ricasso is doing a lot of quiet work.

Hilt

Hilt Overview

The hilt is everything that allows a human hand to survive contact with a sharp, fast-moving blade.

A good hilt:

- Secures the sword in the hand

- Protects fingers and knuckles

- Balances the blade

- Reflects fighting style and period

Guard or Crossguard

The guard sits between blade and grip, stopping opposing blades and hands from sliding down into yours.

Common forms include:

- Straight crossguards on medieval swords

- Curved guards on sabres

- Complex swept hilts on rapiers

More guard does not always mean better protection. Many designs reflect fencing traditions rather than battlefield needs.

Grip

The grip is where function meets comfort.

Most grips feature:

- A wooden core

- Leather, cord, or wire wrap

- Subtle shaping to index the hand

An oval or waisted grip helps alignment, while round grips often appear on thrust-centric swords. If the grip feels wrong, the sword probably is wrong.

Pommel

The pommel sits at the end of the hilt and acts as a counterweight.

It contributes to:

- Overall balance

- Point control

- Structural integrity

Pommel shapes vary wildly across history. Disc, wheel, scent-stopper, and pear forms all signal different eras and preferences. Occasionally, the pommel doubles as a striking surface, though that was never its primary job.

Tang

Tang Overview

The tang is the portion of the blade that extends into the hilt. It is invisible when assembled, which is exactly why it matters.

Full Tang vs Partial Tang

A proper sword should have a tang that:

- Extends most or all the way through the grip

- Is forged as part of the blade, not welded

A narrow or stub tang is a structural weakness. Historically, swordsmiths understood this well. Modern reproductions sometimes do not.

Peened Tang or Threaded Construction

Historically, most swords were peened, meaning the tang was hammered over the pommel to lock everything together.

Threaded construction:

- Is common on modern replicas

- Makes disassembly easier

- Is not historically accurate for most periods

Neither method is automatically bad, but peening remains the gold standard for strength.

Scabbard Components

Scabbard Body

The scabbard protects both blade and wearer.

Traditional scabbards use:

- A wooden core

- Leather or textile covering

- Sometimes metal reinforcement

Bare leather scabbards without a core are a modern shortcut and tend to damage blades over time.

Throat and Chape

The throat reinforces the opening of the scabbard, while the chape protects the tip.

They help with:

- Preventing wear

- Maintaining shape

- Visual identification of period and region

On archaeological finds, these fittings often survive long after organic materials are gone.

Decorative and Structural Details

Blade Inscriptions and Maker’s Marks

These range from religious phrases to workshop signatures.

They can indicate:

- Place of manufacture

- Intended market

- Status of the owner

They can also be faked, which keeps auction specialists awake at night.

Peen Block and Washer Plates

Small details at the pommel end often reveal whether a sword was built with care or rushed out the door.

Collectors pay attention here for good reason.

Why Knowing Sword Anatomy Matters

Understanding sword parts helps you:

- Judge historical accuracy

- Spot unsafe reproductions

- Appreciate design choices

- Speak confidently without sounding like you learned everything from a game menu

It also makes museum visits far more satisfying. Once you see the details, you cannot unsee them.

Common Misconceptions

- A fuller is not a blood groove

- Heavier does not mean stronger

- Sharpness matters less than geometry

- Most medieval swords were not crude or poorly balanced

History was full of skilled engineers, even if they did not call themselves that.

Variations Across Cultures

While these components form the basis of most swords, regional variations add distinctive features. For example:

- Japanese katana include a habaki (blade collar) and tsuba (guard) with decorative fittings.

- European longswords may have complex guards and different pommel shapes.

- Middle Eastern sabres often have curved blades and open or knuckle-bow guards.

Sword Anatomy Reference Table

| Part | Location on the Sword | Primary Function | Notes and Variations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blade | Main body of the sword | Cutting, thrusting, or both | Shape and profile define the sword’s role more than length alone |

| Edge | Sharpened side of the blade | Delivers cuts | Can be single or double edged, thickness affects durability |

| Tip or Point | End of the blade | Thrusting and penetration | Narrow points favour armour gaps, broad points favour cutting |

| Fuller | Groove along the blade | Reduces weight, improves stiffness | Often misunderstood as a blood groove |

| Ricasso | Unsharpened blade section above guard | Allows finger placement and control | Common on rapiers and later swords |

| Spine | Back edge of the blade | Structural support | On single edged swords, adds strength |

| Hilt | Entire handle assembly | Control, balance, protection | Includes guard, grip, and pommel |

| Guard or Crossguard | Between blade and grip | Protects the hand, catches blades | Shape reflects fencing style and period |

| Grip | Where the hand holds the sword | Secure handling and alignment | Often wood with leather, cord, or wire |

| Pommel | End of the hilt | Counterbalance and stability | Shape is often period specific |

| Tang | Blade extension inside the hilt | Structural core of the sword | Should be integral to the blade |

| Peen | End of the tang over pommel | Locks the sword together | Strong and historically common |

| Scabbard | Sword sheath | Protects blade and wearer | Traditionally wood cored |

| Throat | Scabbard opening | Reinforces entry point | Often metal fitted |

| Chape | Scabbard tip | Protects scabbard end | Useful for dating finds |

| Maker’s Mark | On blade or hilt | Identifies workshop or origin | Frequently copied or forged |

| Washer Plate | Between pommel and grip | Stress distribution | Small detail that signals build quality |

The Seven Swords Takeaway

A sword is a system. Every part influences every other part, and when one is poorly executed, the whole thing suffers. Learning the anatomy gives you a sharper eye, whether you are collecting, reenacting, or just quietly judging wall-hangers online.

If nothing else, it gives you the confidence to say, “Nice sword, shame about the tang,” and mean it.

Watch the documetary: