The Carolingian Dynasty shaped early medieval Europe with a force that feels almost improbable when you set their achievements beside the fractured world they inherited. Their story moves from mayors of the palace with more clout than the kings they served to emperors who tried to rebuild a Roman order in a landscape that barely remembered it. I have always found them strangely human in this ambition, both restless and confident, often brilliant and sometimes catastrophically short sighted.

Origins and Rise to Power

The dynasty began within the Merovingian world, a court system where practical power slipped away from kings and settled into the hands of the mayors of the palace. By the time Charles Martel emerged in the early eighth century, the dynasty already had a reputation for hard government and determined expansion. Martel was the one who hammered it into something larger, quite literally, if you believe half the annalists who adore him.

His victory at the Battle of Tours in 732 has been dressed up by later writers who enjoyed turning every frontier skirmish into a defence of western civilisation. What matters more is that Martel managed to stabilise Frankish rule and reward supporters with new lands. This cemented the family’s authority and paved the way for his successors.

Peppin the Short went further. Tired of the fiction of Merovingian kingship, he arranged for papal approval to take the crown for himself. Watching power shift through ritual is one of the most vivid parts of the period and Pippin’s accession shows how tightly politics and spiritual legitimacy could intertwine.

Charlemagne and the Height of Carolingian Rule

Charlemagne is the name that overshadows the rest and I admit I fall into the same habit because he influences every direction you turn. He was relentless in campaign, strategic in his use of church reform and shrewd in his consolidation of territory through law and administration.

His conquests in Saxony were brutal and drawn out. His expansion into Italy, Bavaria and beyond created a realm so large that one wonders how he slept at night knowing that rebellion simmered in multiple corners. Yet he travelled constantly, ruling in motion. The imperial coronation of 800 marked an extraordinary attempt to revive Western imperial authority. Whether he encouraged the coronation or merely accepted it is still argued over in seminars, often with too much coffee and not enough fresh air.

Culturally, Charlemagne presided over a remarkable intellectual revival. Manuscript production, script reform, educational projects and the preservation of classical texts took place during his reign. As a historian, I can say without exaggeration that our shelves would be poorer if not for Carolingian scribes who copied texts with steady hands during cold winters.

Government, Society and Military Structure

Carolingian governance balanced royal authority with the obligations of the aristocracy. Royal capitularies attempted to regulate behaviour across a vast realm but the success of these laws depended heavily on local counts. Their network of missi dominici, royal envoys who travelled in pairs, acted as the eyes and ears of the court. It feels innovative for the period and unusually ambitious.

Militarily, the Carolingians relied on a fusion of mounted warriors, local levies and aristocratic retinues. Their campaigns were seasonal and often relied on rapid movement. Equipment varied by region but elite cavalry with spears, shields and mail dominated the sources. We see a gradual strengthening of cavalry tactics in this period, although some scholars argue we should not picture them as fully developed knightly warriors. The truth is somewhere in the middle.

Fragmentation and Decline

The empire was too large and too dependent on the personality of its rulers. After Charlemagne died, Louis the Pious struggled to keep his sons from tearing the realm apart. Their conflict resulted in the Treaty of Verdun in 843, dividing the empire into three sections that would influence the future shape of Europe.

What followed was a slow unravelling. Raids, internal disputes, regional autonomies and competing claims chipped away at Carolingian cohesion. The dynasty survived in different branches but none regained the reach or confidence of the early ninth century. I admit a strange affection for these later rulers who tried to govern with the weight of a legacy that had already begun to crumble.

Cultural and Historical Legacy

The Carolingians did not restore the Roman world but they created something new and profoundly influential. Their educational reforms shaped medieval learning. Their administrative experiments encouraged later European governance. The geopolitical map drawn by the Treaty of Verdun cast long shadows over the formation of France and Germany.

Every time I read the annals, I am struck by how the dynasty walked a line between aspiration and limitation. They dreamed in imperial scale but governed through fragile networks. Their achievements came from persistence as much as from brilliance.

Where to Explore Carolingian History Today

Traces of the dynasty remain across Europe. Aachen Cathedral carries the weight of Charlemagne’s reign in its octagonal structure. The monasteries of Fulda, St Gall and Corbie preserve manuscript traditions that thrived under Carolingian patronage. Museum collections in Paris, Munich and Vienna hold weapons, liturgical objects and manuscripts that bring the period to life with surprising immediacy.

Standing in these spaces always gives me the sense that the Carolingians understood the power of symbolism. They built, wrote and ruled with an eye toward legacy and we, centuries later, are still negotiating their memory.

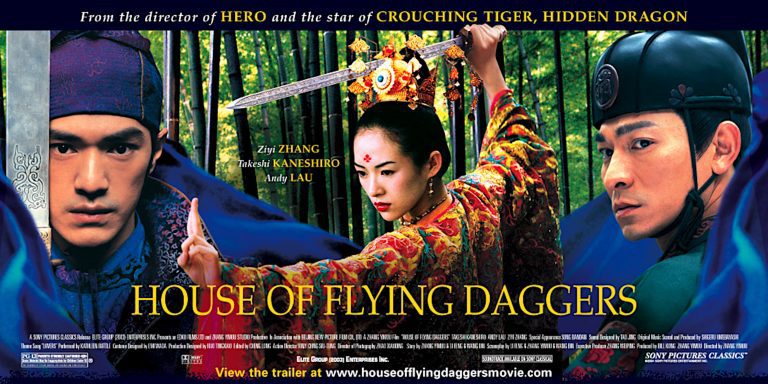

Watch the documentary: