The Ottoman dynasty began as a modest Anatolian ruling house and ended as one of the longest lasting imperial families in recorded history. From the late thirteenth century to the early twentieth, the Ottomans ruled across three continents, governed a mosaic of peoples, and left a political and cultural footprint that still shapes southeastern Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. Few dynasties managed longevity on this scale without collapsing into irrelevance far earlier. That alone earns attention, even before we get to the sultans who combined personal ruthlessness with genuine administrative talent.

Origins of the Dynasty

The dynasty takes its name from Osman I, a frontier warlord operating on the edge of the crumbling Seljuk world around 1299. Osman was not a grand conqueror in the classical sense. He was a pragmatic opportunist, skilled at exploiting Byzantine weakness, local alliances, and the steady flow of ghazi warriors eager for land and status.

What distinguished the early Ottomans was flexibility. They absorbed local elites rather than crushing them, adopted Byzantine administrative habits when useful, and avoided rigid tribal structures. This was not ideological empire building. It was survival first, expansion second, and myth making much later.

Expansion and Imperial Consolidation

The real transformation came in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Orhan formalised governance, Murad I pushed deep into the Balkans, and Bayezid I moved fast enough to alarm both Christians and fellow Muslim rulers. That speed proved dangerous when Timur intervened in 1402 and shattered Bayezid’s army at Ankara.

Many dynasties would have ended there. The Ottomans did not.

After a bruising civil war, Mehmed I restored unity, and his grandson Mehmed II delivered the moment that still defines the dynasty in popular memory. The capture of Constantinople in 1453 was not only symbolic. It provided a capital, a tax base, and a claim to Roman imperial inheritance. From that point on, the Ottomans thought and ruled like emperors, not frontier raiders.

The Classical Ottoman Age

The sixteenth century marked the dynasty at its height. Selim I expanded aggressively east and south, absorbing the Mamluk Sultanate and claiming custodianship of Mecca and Medina. His son, Süleyman I, known in Europe as the Magnificent and at home as the Lawgiver, presided over a state that blended military strength with legal coherence.

Under Süleyman, the dynasty reached from Hungary to Yemen. The army was disciplined, the navy formidable, and the bureaucracy unusually professional for its time. Ottoman law balanced Islamic principles with pragmatic imperial governance, a combination that kept diverse provinces functioning without constant rebellion.

This was also the period when court politics became lethal. Fratricide was legalised as a matter of state security, a policy brutal in execution but effective in preventing prolonged succession wars. Historians still debate whether this was cold realism or dynastic paranoia. It was probably both.

Court Life and Succession

The Ottoman dynasty was not sustained by battle alone. It survived through careful management of succession, marriage, and household politics. The imperial harem, often misunderstood or sensationalised, was a political institution. Mothers of sultans, the valide sultans, could wield enormous influence, particularly during periods of weak or young rulers.

Over time, succession practices softened. Fratricide gave way to confinement, with potential heirs kept in the palace rather than executed. This spared lives but produced rulers who ascended the throne with limited experience beyond gilded rooms and court intrigue. Unsurprisingly, governance suffered.

It turns out that locking future emperors in comfortable isolation does not reliably produce decisive leadership. History has been kind enough to test this theory repeatedly.

Decline, Reform, and Survival

From the late seventeenth century onwards, the dynasty faced structural problems rather than sudden collapse. Military technology lagged behind European rivals, provincial governors gained autonomy, and economic power shifted away from traditional trade routes.

Yet the Ottomans proved remarkably adaptable. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw waves of reform, from military restructuring to legal modernisation. The Tanzimat era attempted to recast the dynasty as constitutional, rational, and compatible with modern statehood.

These efforts were serious, often intelligent, and ultimately insufficient. External pressure, nationalist movements, and the disaster of the First World War overwhelmed the imperial system. In 1922, the sultanate was abolished, ending over six centuries of dynastic rule.

Legacy of the Ottoman Dynasty

The Ottoman dynasty left a complicated inheritance. Architecturally, cities like Istanbul, Edirne, and Bursa remain shaped by imperial ambition. Administratively, the Ottomans demonstrated that a multi religious empire could function without constant coercion, at least when leadership was competent.

Politically, the dynasty serves as a reminder that longevity is not the same as stagnation. The Ottomans endured because they adapted, reformed, and compromised, even when ideology might have preferred rigidity. Their failure came not from refusal to change, but from changing too slowly in a world that had begun to sprint.

For a family that began with a single warlord and ended as a global empire, that is not a bad historical run.

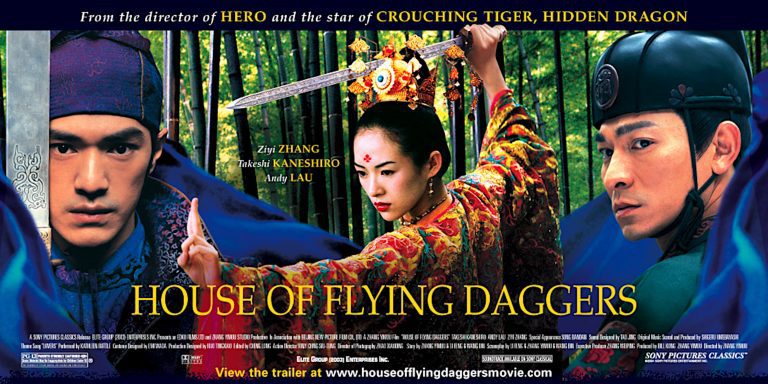

Watch the documentary: